Being an animal, human or not, is not easy peasy. In order to survive and make lots of babies, one must get enough resources, such as food, territory, and mates (the sexual kind, of course). More often than not, this implies competing for those resources with others, especially conspecifics (members of the same species). So, to be successful and thrive, one needs to have certain strategies to deal with the competition. What have animals evolved for that?

In nature, resources are often limited; therefore, being able to correctly estimate the number of rivals you have can allow you to optimise your behaviour in a way that increases your chances of winning. For instance, you may choose to give up fighting if there are too many opponents.

In birds, the young depend, for their survival, entirely on the food provided by their parents. Yet, this food has to be shared with their siblings. This leads to competition between members of the same brood, explaining why nestlings beg to get the attention of their parents – they might get more food.

Because begging behaviours often come at a cost (e.g., predation; see Leech & Leonard, 1997), nestlings won’t do them if they are not too hungry. Ornithologists have discovered that the effort invested by nestlings in sib-sib competition (i.e., between siblings) can depend on their level of need, their ability to compete, or even the location of siblings in the nest. However, it is not known whether they modify their behaviour in response to the number of siblings present.

At the University of Lausanne, in Switzerland, researchers have investigated the numerical ability of nestling barn owls Tyto alba (Ruppli, Dreiss & Roulin, 2013). In these birds, parents bring to the nest small indivisible prey (often mammals) to feed their offspring. They do so at irregular time intervals so that their arrivals are unpredictable. In their absence, nestlings communicate vocally with each other – they negotiate – to determine who gets the food next time (Johnstone & Roulin, 2003).

Knowing that, the researchers devised a protocol to evaluate nestlings’ ability to count. They began by recording nestling calls emitted in nature from several broods. Then, they assembled those calls to create different combinations (playbacks) of both number of individuals and number of calls. They broadcasted these playbacks to singleton nestlings and measured, in particular, the number of calls that those “participants” emitted in response.

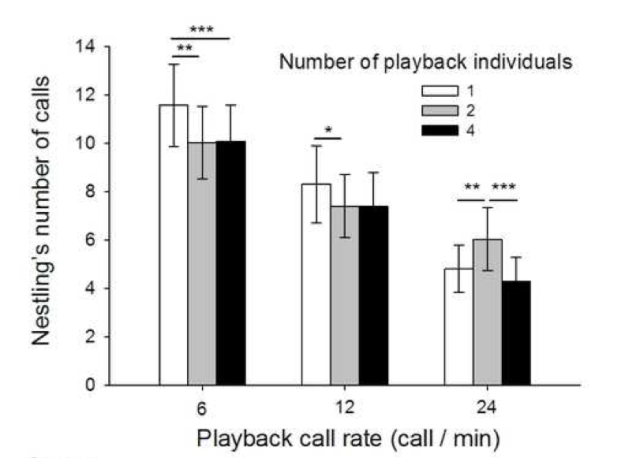

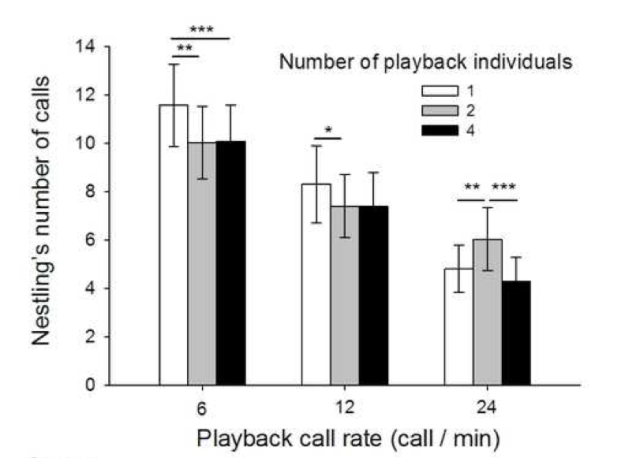

Number of calls emitted by singleton nestlings (mean and standard error of mean) in response to varying number of playback individuals and varying playback call frequencies. The lines accompanied by one or more asterisks depict statistically significant differences, i.e., big enough that they’re probably not due to chance only (copied from Ruppli et al. 2013).

The results of this study show that nestlings called more or less depending not only on call frequency in the playback (number of stimuli), but also on the number of calling individuals. By the way, nestling barn owls seem to possess individual recognition abilities (pers. comm.), which is further supported by these results. According to the authors, it indicates that barn owl nestlings are capable of discriminating the number of competing individuals in the nest and using this information to adjust their own behaviour.

In short, this means that these birds possess a certain numerical ability, at least for small quantities in the context of sib-sib competition. It is not yet known whether this ability is maintained throughout life as the birds’ ecology changes.

This finding is important because it provides clues for understanding the function of numerical abilities and the factors which may have contributed to their evolution. In a way, it could lead to some insight into the emergence of mathematics in humans. Who knows, maybe they do not exist only as an instrument of torture for pupils/students…

Reference

Johnstone, R. A., & Roulin, Al. (2003). Sibling negotiation. Behavioral Ecology, 14(6), 780-786. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arg024

Leech, S. M. & Leonard, M. L. (1997). Begging and the risk of predation in nestling birds. Behavioral Ecology, 8(6), 644-646.

Ruppli, C. A., Dreiss, A. N., & Roulin, A. (2013). Nestling barn owls assess short-term variation in the amount of vocally competing siblings. Animal Cognition, 16(6), 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0634-y

PS: Many thanks to fellow grad student Tania Studer for her help in editing this post.